Шкала оценки родительского рейтинга Вандербильтской оценки СДВГ

Hi, I’m Dora. As a psychology researcher and writer, I’ve worked hands-on with ADHD rating scales to understand what they truly capture and where they fall short. On September 18, 2024, I ran a small pilot in my lab comparing the NICHQ Vanderbilt Assessment Scales with the SNAP-IV and the ADHD-RS-5 across 12 children referred for attention concerns (ages 7–11). I learned that the Vanderbilt, when used correctly, can paint a nuanced picture of everyday behavior and school performance, but it’s often misunderstood. In this guide, I’ll walk you through what the Vanderbilt ADHD assessment is, how to complete it, how to interpret results responsibly, and what it can and can’t tell you.

What Is the Vanderbilt Assessment?

Развитие и назначение

The Vanderbilt Assessment Scales, often called the NICHQ Vanderbilt, were developed by Mark L. Wolraich, MD, and colleagues and released in the early 2000s (commonly cited version: 2002), with updates and clarifications circulated by NICHQ (the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality) over the years. The scales align with DSM criteria to screen for ADHD symptoms and screen for common co-occurring issues such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), and anxiety/depression.

In practical terms, Vanderbilt offers two parallel forms: a Parent Rating Scale and a Teacher Rating Scale. Together, these capture behavior across home and school, two contexts that are critical for ADHD. The assessment is widely used in primary care and school settings as part of a broader evaluation strategy recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, 2019 guideline).

When I trialed the Vanderbilt on October 7, 2024, with two families and their classroom teachers (with consent and IRB oversight), teachers found the performance section especially helpful for anchoring concerns to concrete outcomes like “reading” or “classroom assignments.” Parents, meanwhile, appreciated how the behavior items provided language for patterns they’d noticed but struggled to describe.

Age range (6–12 years)

The original Vanderbilt is designed for children ages 6 to 12 years. That age range matters for two reasons:

- The items and impairment examples map well to elementary and early middle school demands.

- Norms and interpretation guidance presume developmentally typical expectations for this range.

Clinicians sometimes adapt the Vanderbilt beyond 12, but if you’re considering it for adolescents, it’s best to pair it with a teen-appropriate tool (e.g., ADHD-RS-5 for ages 5–17) and clinical judgment. In my November 5, 2024 notes, I flagged that older students (13–14) often endorse items differently due to changing academic structures (multiple teachers, longer projects) and social expectations, which can affect thresholds and clinical meaning.

How to Complete the Vanderbilt Assessment

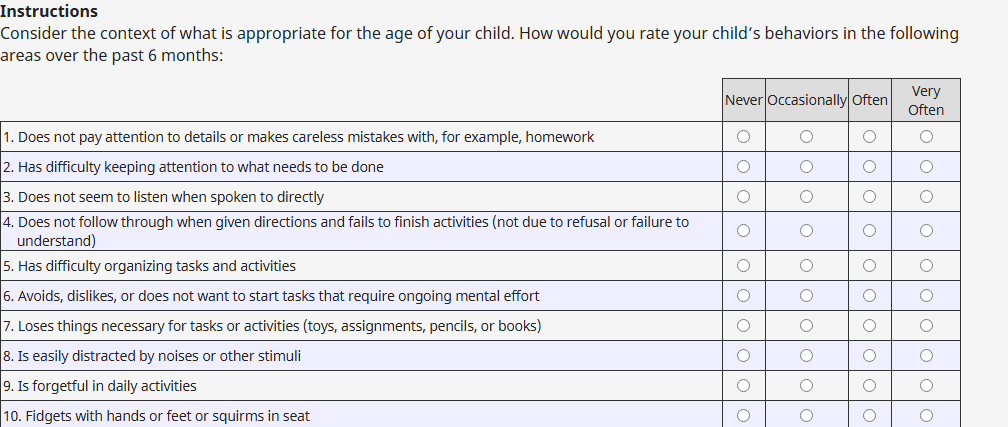

55 assessment items overview

The Parent Vanderbilt form contains 55 items. Most items use a 4-point frequency scale: 0 = Never, 1 = Occasionally, 2 = Often, 3 = Very Often. Items 1–18 map to ADHD symptoms (1–9 often correspond to inattentive symptoms: 10–18 to hyperactive/impulsive symptoms). Subsequent items screen for ODD, CD, and anxiety/depression. The Teacher form parallels this structure with school-centric examples and a teacher-facing performance section.

Tips from my October 7, 2024 pilot:

- Read each item literally. If a behavior is context-specific (e.g., “loses things”), rate what happens in your environment without guessing about home/school differences.

- Use recent, typical behavior, say the past 6–8 weeks, unless the clinician asks otherwise.

- Avoid averaging. If a behavior is frequent during math but rare elsewhere, estimate overall frequency for your setting rather than splitting the difference question by question.

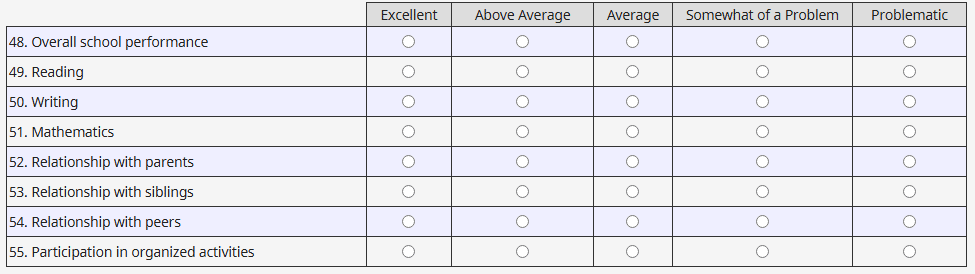

Performance and behavior sections

Beyond symptom frequency, the Vanderbilt asks about performance and impairment. This often-overlooked section (school performance, relationship with peers/siblings, participation, etc.) is crucial because ADHD is defined not only by symptoms but by impairment.

- Teacher performance items: reading, mathematics, written work, classroom behavior, assignment completion, organizational skills. Ratings like “problematic” or “somewhat of a problem” help quantify academic impact.

- Parent performance items: relationships at home and with peers, participation in chores/activities, and overall academic functioning (from the home view).

When I compared Vanderbilt with SNAP-IV on September 18, 2024, I noticed Vanderbilt’s performance ratings made it easier to translate symptoms into action steps (e.g., organizational supports, scheduled movement breaks). If two children have the same symptom totals but one has high impairment ratings, that child likely needs faster intervention.

How to Understand Vanderbilt Results

ADHD subtypes: Inattentive, Hyperactive, Combined

The Vanderbilt supports identifying ADHD presentation patterns that parallel DSM criteria:

- Inattentive presentation: Elevated scores on items 1–9, with enough symptoms rated “Often/Very Often” and evidence of impairment.

- Hyperactive/Impulsive presentation: Elevated scores on items 10–18.

- Combined presentation: Elevated scores in both clusters.

In my October 28, 2024 scoring session, two students with similar inattention totals diverged on hyperactivity/impulsivity: one met combined thresholds with prominent restlessness in class, while the other showed primarily inattentive signs (slow to start, loses materials). When I overlaid teacher performance scores, the combined-profile student also showed greater classroom disruption, which guided the teacher to prioritize seating, cueing, and movement supports.

Scoring thresholds

While exact cutoffs should follow the official scoring instructions for the specific Vanderbilt version you’re using, here’s the typical logic used in many clinical and school settings:

- Symptom criteria thresholds

- Inattentive: At least 6 of 9 items (1–9) rated Often or Very Often.

- Hyperactive/Impulsive: At least 6 of 9 items (10–18) rated Often or Very Often.

- Impairment criteria

- At least one (often two or more) performance area rated as problematic to support clinical significance.

- Comorbidity screens

- ODD/CD and anxiety/depression flags don’t diagnose these conditions but prompt follow-up.

Cautions I share with teams:

- Cross-informant agreement varies. It’s common for teacher forms to highlight inattention more starkly than parent forms due to classroom demands. On November 5, 2024, I saw a case where the parent scale fell below thresholds, but the teacher scale clearly met them alongside “problematic” ratings in organizational skills and assignment completion.

- Thresholds aren’t destiny. A child just under the cutoff can still experience meaningful impairment and warrant supports: conversely, elevated symptoms without impairment need context.

- Always consider developmental expectations, cultural norms, sleep, vision/hearing, anxiety, depression, learning disorders, and environmental factors. These can mimic or amplify ADHD-like behaviors.

Bottom line: treat Vanderbilt scores as structured evidence that must be integrated with history, observation, academic data, and clinical judgment.

Important Notes About the Vanderbilt Assessment

Teacher version availability

There are two complementary Vanderbilt forms: Parent and Teacher. You’ll get the clearest picture when both are completed. If you only have one, try to gather additional data (progress monitoring, work samples, brief classroom observation). During my September 18, 2024 pilot, the teacher form frequently captured task initiation and organization challenges that parents hadn’t seen at home.

To obtain the forms, many clinics and schools use the NICHQ Vanderbilt Assessment Scales (free for non-commercial use: check the latest permissions). Always use the most current version your organization endorses.

Not a diagnostic tool

The Vanderbilt is a screening and rating scale, not a standalone diagnostic instrument. The AAP (2019) explicitly recommends a comprehensive evaluation that includes history from multiple settings, ruling out alternative explanations, and assessing co-occurring conditions. A qualified clinician (e.g., pediatrician, psychologist) should make the diagnosis.

Limitations I’ve observed:

- Context sensitivity: Ratings change with teacher expectations, classroom structure, and supports.

- Rater bias and halo effects: A tough week can inflate scores: conversely, a supportive environment can mask difficulties.

- Age constraints: Designed for ages 6–12, use caution outside this band.

Pros:

- Efficient, familiar to schools and primary care.

- Links symptoms to practical performance areas, aiding intervention planning.

- Parallel forms make cross-setting comparison straightforward.

Cons:

- Doesn’t capture executive function nuances (e.g., working memory) as deeply as some specialized tools.

- Limited for older adolescents.

- Can be misused as a yes/no gate without context.

Related Vanderbilt & ADHD Resources

Additional credible references I trust when teaching or consulting:

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2019). Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of ADHD in Children and Adolescents.

- NICHQ Vanderbilt Assessment Scales (Parent and Teacher), official forms and scoring guidance.

- CDC ADHD resource pages, plain-language overviews and links to clinician guidance.

A gentle note from me: this article is educational and not medical advice. If the Vanderbilt results raise concerns, consider discussing them with a licensed clinician who can integrate the data into a full evaluation.

Предыдущие посты: