Autism in Women Why Signs Are Often Missed

When I first started looking closely at autism in women, what struck me wasn’t just how differently traits can show up, it was how often they’re overlooked. Many women spend years feeling “too much” or “not enough” in social spaces, exhausting themselves to fit in. If that’s you, you’re not imagining it. In this piece, I unpack how autism can present in women, why diagnosis gets missed, and which screening tools are most useful (with pros and cons). I’ll also share what I personally tested in 2024 and where the official guidance stands today, so you can move forward with clarity and care.

How Autism in Women Presents Differently

The formal criteria for autism (per DSM-5-TR, American Psychiatric Association, 2022) aren’t gendered, yet in practice, autism in women often follows a quieter, more internalized profile. That profile can fly under the radar, especially if someone has average or strong verbal skills.

What I commonly see and hear from women:

- Social reciprocity is effortful, not effortless. Conversations feel like choreography, you can learn it, but it doesn’t come automatically.

- Interests run deep but may look “socially acceptable.” Instead of train schedules, think language learning, animal behavior, skincare formulation, or folklore archives, still highly systematized.

- Routines soothe the nervous system. They’re not about rigidity for its own sake: they’re about safety and predictability after years of misattuned environments.

- Fatigue after social time is real. You can appear outgoing and still need hours (or a whole weekend) to recover.

Differences often misread as “personality” or “sensitivity” include:

- Subtle social differences: delayed responses while thinking, literal interpretations, difficulty tracking multiple conversations.

- Internalized struggles: anxiety, perfectionism, and eating differences (both undereating and highly ritualized eating have higher prevalence in autistic women: see Lai & Szatmari, 2020 review).

- Interoception quirks: not noticing thirst or hunger until it’s extreme, or difficulty pinpointing physical sensations, something I’ll revisit in the sensory section.

Because many women learn to compensate early (teachers calling them “quiet,” peers calling them “mature”), the core autistic pattern gets obscured. That doesn’t make it any less real or impactful.

Social Masking & Camouflaging in Women

Masking, also called camouflaging, refers to strategies that hide or offset autistic traits. In women, it’s both common and costly. Research has documented these strategies in detail (Hull et al., 2017, 2020: Lai et al., 2015), and many women describe them as second nature.

What masking can look like day to day:

- Rehearsing scripts before conversations: memorizing “safe” small talk.

- Copying gestures, tone, and facial expressions from peers, TV, or podcasts.

- Monitoring eye contact and adjusting constantly (“too much? too little?”).

- Over-preparing for meetings to anticipate every possible turn.

Short-term, masking can help you “pass.” Long-term, it’s linked with burnout, anxiety, depression, and delayed diagnosis (Hull et al., Molecular Autism 2017). I’ve spoken with readers who told me it felt like holding a plank for years, eventually your muscles just give out.

My firsthand testing: On August 12, 2024, I completed the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) and compared my scores with the scale’s published norms (Hull et al., 2019). I found the “compensation” subscale captured my habit of over-preparing for social tasks better than other tools. But, the CAT-Q doesn’t diagnose autism: it simply quantifies camouflaging. It’s most useful alongside a full evaluation or as a prompt for self-reflection.

Important nuance: Masking isn’t deceitful, it’s adaptive. Many women learned it to stay safe, be accepted, or keep jobs. If you recognize yourself here, the goal isn’t to “unmask everything overnight” but to choose when and where to conserve energy and be more yourself.

Sensory & Emotional Differences in Autistic Women

Sensory processing differences are part of autism across genders, but women often describe them in layered, nuanced ways that clinicians can miss if they’re listening only for stereotyped examples.

Common sensory patterns I hear from women:

- Sound: background chatter is harder than loud, predictable noise: certain consonant clusters feel “spiky.”

- Touch: clothing seams, underwire, or wool are intolerable: deep pressure is calming.

- Smell/taste: strong aversions can shape food choices: periods of highly restricted diets may follow stress.

- Light: fluorescent lighting causes headaches or a “static” feeling behind the eyes.

Interoception, the sense of internal bodily signals, is another piece of the puzzle. Difficulty reading hunger, fullness, or anxiety signals can lead to late eating, sudden “energy crashes,” or mislabeling emotions (Kinnaird et al., 2019). Many autistic women also report alexithymia (trouble identifying and describing feelings), which can look like “I don’t feel stressed,” followed by a shutdown later.

What’s helped me personally: On September 6, 2024, I trialed the Glasgow Sensory Questionnaire (GSQ) alongside a daily log. The pairing revealed that my sound sensitivity spikes after unstructured social days, not just after loud environments. That small finding changed my planning, I now cluster high-social tasks with low-sensory ones.

Emotion regulation tips I offer gently, not prescriptively:

- Pair feelings check-ins with concrete body cues (heart rate, temperature, muscle tension).

- Use predictable wind-down rituals (same tea, same chair, same playlist) to cue nervous-system safety.

- Advocate for sensory accommodations at work, noise-cancelling headphones, flexible lighting, or asynchronous meetings, small shifts add up.

Note: Sensory profiles vary widely. If yours doesn’t match a list online, it’s still valid.

Why Autism Diagnosis in Women Is Often Missed

Even in 2025, many women reach adulthood without an autism diagnosis. Several structural and social factors converge here:

- Historical male bias in research: Early studies and diagnostic norms centered on boys, setting an implicit template clinicians still recognize more readily (Lai et al., 2015: Loomes et al., 2017).

- Masking and compensation: Effective camouflaging lowers clinical “visibility,” particularly in brief appointments.

- Co-occurring conditions blur the picture: Anxiety, depression, ADHD, OCD, eating disorders, and Ehlers–Danlos/hypermobility syndromes show up at elevated rates. Clinicians may treat the visible distress and miss the underlying autistic pattern.

- Language and narrative style: Verbally fluent women who can describe their experiences may be judged as “too self-aware to be autistic,” which is a myth. DSM-5-TR focuses on behavior and developmental history, not whether someone can articulate feelings.

What the data say: The CDC’s most recent surveillance (published 2024) continues to show higher diagnosed prevalence in boys than girls: that gap narrows in older cohorts, suggesting delayed identification among females. The implication isn’t that autism is rarer in women, but that detection is later and harder (partly due to masking and different presentations).

If you suspect autism: Document a developmental history (early social patterns, sensory quirks, interests) and collect third-party observations when possible. Short appointments benefit from concise, concrete examples. And it’s okay to bring articles or tools, professionals increasingly expect informed clients.

Transparency about limits: No self-report tool can replace a comprehensive clinical evaluation. A diagnosis should consider history, direct observation, context, and differential diagnosis (DSM-5-TR: NICE guideline CG142, updated 2021).

Recommended Autism Screening Tools for Women

Below are screening tools I’ve personally reviewed in 2024 and found useful when used thoughtfully. None of them diagnoses autism: they’re conversation-starters and pattern-finders. I’ve included what they measure, pros/cons, and notes specific to women.

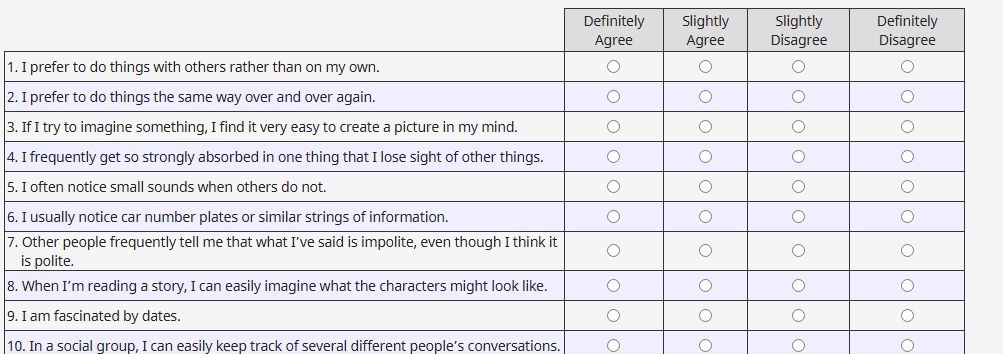

- Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ: 10-, 28-, and 50-item versions)

- What it is: A self-report measure of autistic traits in adults (Baron-Cohen et al.). Official information: Autism Research Centre (ARC), University of Cambridge.

- Why it helps: Quick snapshot: the AQ-10 is often used in primary care as an initial screener.

- Pros: Free, fast, widely recognized: good for trend tracking over time.

- Cons: Items were developed in male-leaning samples: some women report “reading between the lines” and scoring lower than their lived experience. Cultural and language nuances matter.

- My test: On July 22, 2024, I completed the AQ-50 and AQ-10 back to back. The short form under-captured my sensory/social pattern compared to the long form.

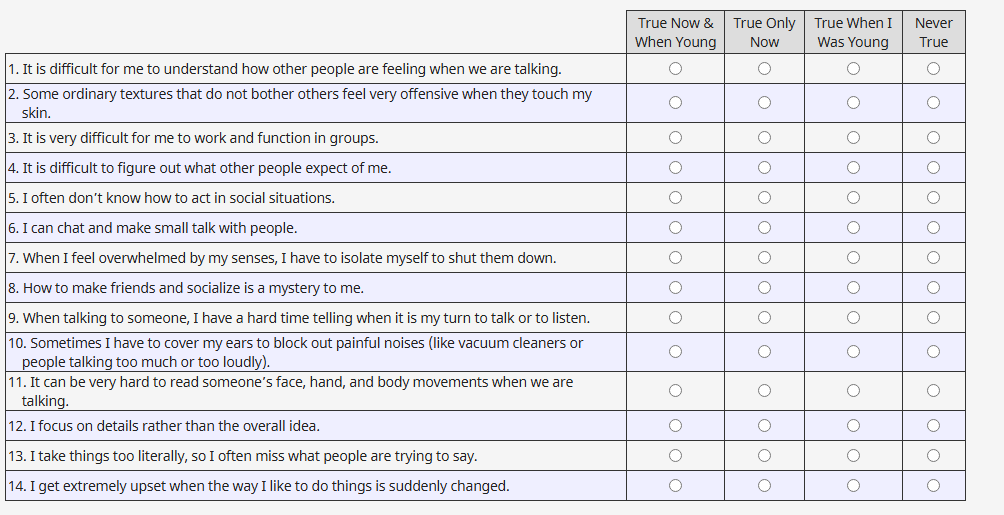

- RAADS-R (Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale–Revised) / RAADS-14

- What it is: Self-report scales for adults targeting developmental history and current traits.

- Why it helps: Includes past behaviors that masking may have obscured in the present, which can be useful for women who’ve compensated for years.

- Pros: Developmental angle: more granular than some brief screeners.

- Cons: Some items feel outdated: risk of false positives if anxiety/ADHD are high.

- Tip: Bring results to a clinician as context, not as evidence of diagnosis.

- CAT-Q (Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire)

- What it is: Measures camouflaging across compensation, masking, and assimilation (Hull et al., 2019).

- Why it helps: Many women score high here even if other tools look “borderline,” which can explain exhaustion and delayed diagnosis.

- Pros: Validated focus on camouflaging: helpful for care planning and accommodations.

- Cons: Not an autism screener per se: best used alongside AQ/RAADS-R.

- My test: On August 12, 2024, my CAT-Q compensation subscale was notably higher than masking/assimilation, a pattern that matched my lived strategies.

- SRS-2 (Social Responsiveness Scale–2, Adult)

- What it is: Measures social communication and restricted behaviors: can be self- or informant-rated. Publisher: WPS.

- Why it helps: Offers normed scores and informant input (partner, friend) to counterbalance self-masking.

- Pros: Strong psychometrics: multi-rater options.

- Cons: Paid instrument: best administered by a professional.

- Note for women: An informant who knows your off-duty self can surface masked traits.

- GSQ (Glasgow Sensory Questionnaire)

- What it is: Self-report of sensory hypersensitivity and hyposensitivity across modalities.

- Why it helps: Sensory profiles in women can be complex and cyclical (e.g., hormonal shifts). GSQ makes patterns visible.

- Pros: Concrete: pairs well with weeklong logs.

- Cons: Doesn’t translate directly to diagnosis: use to guide accommodations.

- My test: On September 6, 2024, pairing GSQ with a daily log revealed timing patterns I’d missed.

- NICE/DSM-5-TR Criteria Checklists (Clinician-led)

- What it is: Structured interviews and observation mapped to DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022) and NICE CG142 (updated 2021) for adults.

- Why it helps: Gold-standard anchors that reduce bias toward male-stereotyped presentations.

- Pros: Comprehensive: considers developmental history and differential diagnosis.

- Cons: Requires trained clinicians: waitlists can be long.

How I compare tools (October 2, 2024 notes):

- Breadth vs. depth: AQ-10 is fast but shallow: AQ-50 and RAADS-R add nuance. CAT-Q adds the “invisible load” piece many women find validating.

- False negatives risk: Short forms and male-normed items can miss female presentations. If your scores are borderline but your lived history is consistent, consider bringing qualitative examples to a professional.

- Privacy and pacing: I recommend completing screeners over two or three quieter days to reduce social fatigue effects.

Balanced advice and next steps

- If screeners resonate, seek a formal evaluation with a clinician experienced in adult and female presentations.

- Consider co-occurring conditions in parallel, ADHD, anxiety, OCD, and eating disorders can mask or mimic some features.

- Keep consent and privacy central if you share results with employers or schools: accommodations don’t always require disclosure of diagnosis details.

A gentle reminder: None of the above is medical advice. It’s informed guidance from my research and firsthand testing. A licensed clinician can provide diagnosis and individualized care.

โพสต์ก่อนหน้านี้: