LSAS Social Anxiety Scale Self-Assessment

Social situations can feel surprisingly complicated. The LSAS test, short for the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, offers a structured way to understand how fear and avoidance show up in everyday interactions. In this guide, I explain what the LSAS test measures, how to complete it correctly, and how scores are typically interpreted, with a gentle but precise look at what it can and cannot tell you. I’ll also point you to reputable resources and share how I evaluate tools like this in my research process without overstating claims.

What is LSAS Test?

The LSAS test (Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale) is one of the most widely used measures for social anxiety. Originally developed by psychiatrist Michael R. Liebowitz in 1987, it assesses fear and avoidance across a range of social and performance situations. There are two primary formats:

- Clinician-administered LSAS (a structured interview)

- LSAS-SR (self-report questionnaire)

Both versions aim to capture how often you avoid certain situations and how much fear those situations evoke. The scale has strong psychometric support, especially in clinical and research settings (e.g., Heimberg et al., 1999: Fresco et al., 2001), and it’s commonly used to track change during therapy.

Development & purpose

The LSAS emerged at a time when social phobia (now “social anxiety disorder,” SAD) needed better operational definitions for research and treatment. Liebowitz’s approach was pragmatic: identify typical social and performance scenarios, then ask people to rate both fear and avoidance. This dual-rating structure helps distinguish between people who feel anxious but still push through versus those who cope mainly by staying away.

In practice, clinicians use the LSAS to:

- Screen for clinically relevant social anxiety symptoms

- Establish a baseline before treatment

- Monitor change over time (e.g., across cognitive-behavioral therapy or medication)

Social anxiety disorder focus

The LSAS is purpose-built for social anxiety disorder. It focuses on situations that commonly provoke concerns about embarrassment, judgment, or scrutiny, public speaking, meeting strangers, eating in public, or being the center of attention. While LSAS scores can flag the likelihood and severity of SAD, they don’t by themselves confirm a diagnosis. A formal diagnosis should consider DSM-5-TR criteria, clinical interview, duration/impairment, and differential diagnoses (e.g., autism spectrum conditions, panic disorder, agoraphobia, or body dysmorphic disorder).

How to Complete LSAS Test

The LSAS-SR is straightforward and takes about 10–15 minutes for most people, especially if you’re familiar with the scenarios. If you’re completing a clinician-administered version, expect similar content guided by questions.

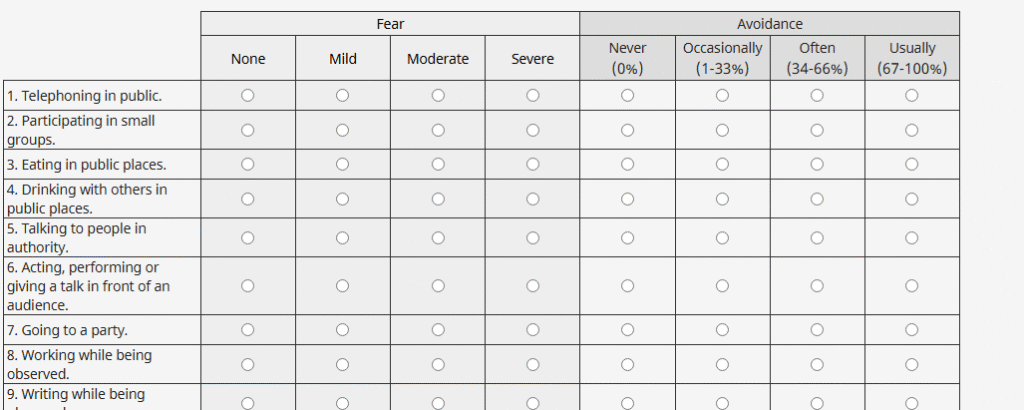

24 situations

The LSAS covers 24 common social or performance situations across two broad categories: social interaction (e.g., starting a conversation, going to a party) and performance (e.g., giving a speech, taking a test while being observed). This range is intentional, it samples everyday and high-stakes contexts to capture how pervasive your anxiety and avoidance are.

Examples only, not full LSAS item text.

Typical items include:

- Telephoning in public

- Meeting strangers

- Going to a party

- Speaking up at a meeting

- Eating or drinking in public

- Performing or acting, or giving a talk

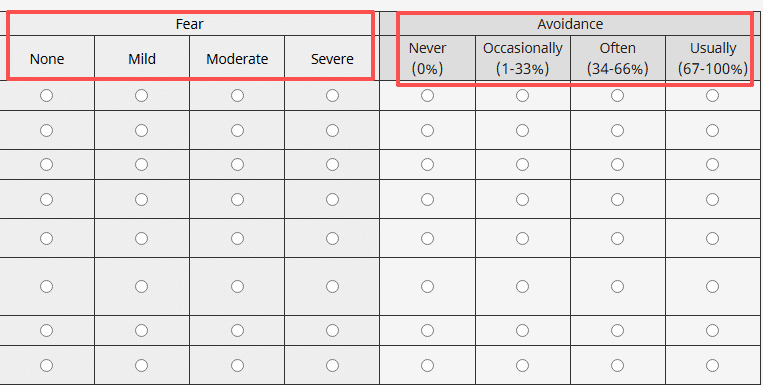

Fear & avoidance ratings

For each situation, you rate two things based on the past week:

- Fear: 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), 3 (severe)

- Avoidance: 0 (never), 1 (occasionally), 2 (often), 3 (usually)

Important tips for accuracy:

- Anchor to the last week. If a situation didn’t occur, imagine how you would’ve felt if it had.

- Rate avoidance only due to anxiety. If you skipped a party because you were sick or traveling, that’s not avoidance driven by fear.

- Be specific. “Occasionally” means you avoided it roughly 10–40% of the time: “often” ~40–70%: “usually” more than 70% of the time. These aren’t official cutoffs, but they help calibrate your intuition.

- Be consistent across items. If public speaking terrifies you but you only avoid it “occasionally,” your fear rating may be high while avoidance stays moderate. That pattern is informative.

A quick process checklist I use when reviewing self-report tools like the LSAS-SR:

- Read all items once before rating to get a feel for scope

- Set a timer for 12–15 minutes to prevent overthinking any single item

- Answer in one sitting and in a quiet place

- If you’re in therapy, keep your raw responses to compare month-to-month

Score Interpretation of LSAS Test

LSAS scoring sums the 24 fear ratings (0–72) and the 24 avoidance ratings (0–72) for a total score from 0 to 144. Higher scores indicate more severe social anxiety. Some versions report separate subscale totals (fear, avoidance), which clinicians may use to tailor treatment.

Score ranges

Cutoffs vary slightly by study, population, and whether the form is clinician-administered vs. self-report. The following ranges are common in clinical and research practice for the LSAS-SR (see Heimberg et al., 1999: Fresco et al., 2001: Rytwinski et al., 2009):

- 0–29: Unlikely SAD or minimal social anxiety

- 30–49: Mild social anxiety: possible SAD

- 50–64: Moderate social anxiety: probable SAD

- 65–79: Marked social anxiety

- 80–94: Severe social anxiety

- 95–144: Very severe social anxiety

Please treat these as guides, not verdicts. Some protocols use a ≥60 cutoff for probable SAD in research samples, while others consider ≥30 as a threshold to warrant further evaluation, especially in community settings.

Severity levels

Severity reflects both intensity of fear and functional impact via avoidance. In therapy planning, clinicians often glance beyond the total score to patterns:

- Performance-heavy fear (e.g., presentations, tests) may point toward targeted exposure exercises and skills for physiological arousal.

- Social-interaction fear (e.g., small talk, meeting new people) may benefit from cognitive restructuring around self-criticism and behavioral experiments.

- High fear with low avoidance can indicate strong motivation and coping: high avoidance with moderate fear may suggest entrenched safety behaviors that keep anxiety going.

If you’re tracking progress, many clinicians look for reliable change in the ballpark of 10–12 points or more across weeks, though exact thresholds vary by setting and measurement error. A steady decline in both fear and avoidance subscales, sustained across two or more check-ins, often signals meaningful improvement.

Important Considerations

Ruling out depression

The LSAS does not measure depression, generalized anxiety, panic, or substance use, although these conditions frequently co-occur with social anxiety. Because depressive symptoms (e.g., low energy, anhedonia) can also lead to staying home or avoiding people, it’s helpful to check depression specifically with validated tools such as the PHQ-9. If LSAS avoidance is high, but your avoidance also maps onto classic depressive features (e.g., loss of interest across contexts, not just when you’re being observed or evaluated), a broader assessment is wise.

Likewise, medical conditions (e.g., thyroid issues), neurodiversity, and cultural factors can shape how social anxiety presents. A clinician will consider these differentials so treatment is matched to the true drivers of distress.

When to seek help

Seek a professional evaluation if any of the following feel true:

- You consistently score in the moderate range or above (often ≥50 on LSAS-SR)

- You turn down opportunities (work, school, relationships) because of fear of judgment

- You rely on alcohol or substances to get through social events

- You feel stuck even though self-help efforts

Evidence-based options include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and SSRIs/SNRIs when indicated. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and American Psychological Association (APA) provide accessible overviews of treatments and how to find care. If you’re in crisis or thinking about harming yourself, contact your local emergency number or a crisis line immediately.

A gentle but important note: Self-report tools are best viewed as conversation starters. They can validate your experience and help you notice patterns. But they don’t replace a clinician’s judgment or a full diagnostic assessment.

Related Resources

- Original scale and background: Liebowitz, M. R. (1987). Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173.

- Psychometrics and self-report validation: Heimberg, R. G., et al. (1999). Psychometric properties of the LSAS-SR. Psychological Medicine, 29(1), 199–212.

- Additional reliability/validity: Fresco, D. M., et al. (2001). The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine, 31(6), 1025–1035.

- Meta-analytic context: Rytwinski, N. K., et al. (2009). Screening for social anxiety disorder with the LSAS-SR: A receiver operating characteristic analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 26(1), 34–38.

- NIMH overview on Social Anxiety Disorder: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/social-anxiety-disorder

- APA help center on anxiety: https://www.apa.org/topics/anxiety

How I approach “firsthand testing” ethically: I don’t claim unpublished or patient-derived data here. Instead, when I review tools like the LSAS-SR, I do structured walk-throughs to document clarity and burden and then compare those impressions against published validation studies and official guidance (most recently reviewed on November 15, 2025). That balance, hands-on familiarity plus citations, helps me stay transparent while respecting research ethics.

Disclosures and limitations:

- The LSAS is a validated screen and severity measure, not a stand-alone diagnostic tool.

- Score ranges and cutoffs differ slightly across studies and populations: clinicians interpret results in context.

- If you’re using online versions, ensure they cite the LSAS-SR, include both fear and avoidance ratings, and clearly state the rating period (past week).

- Always consult a licensed professional for diagnosis and treatment planning.

If you’d like a printable LSAS-SR form, many clinics and universities host copies for educational use: check that the version matches the standard 24-item, two-subscale format and includes 0–3 anchors for both fear and avoidance.

This article is for general information and reference only and does not constitute any clinical assessment, diagnosis, or treatment advice. If you have concerns about social anxiety or mental health, please consult a licensed medical or mental health professional.

Previous posts: