ASRS Test Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (2025 Guide)

Hi, I’m Dora. I remember the first time I tried the ASRS ADHD test. It was a quiet morning on May 14, 2024, and I wanted to see how this brief screener stacked up against longer tools I use in research. As a psychology researcher, I’m often asked whether the ASRS is accurate, how to score it, and what high scores really mean. In this guide, I’ll walk you through the ASRS ADHD test in plain language, what it assesses, how to take it properly, and how to interpret the results safely and responsibly.

What Is the ASRS ADHD Test?

The ASRS (Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale) is a brief screening questionnaire for adult ADHD symptoms. It was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) collaborating with researchers including Ronald Kessler. Two widely used versions exist:

- ASRS v1.1 Symptom Checklist (released mid-2000s: the 6-item screener dates to 2005)

- ASRS-5 (updated for DSM-5: published around 2017)

Both versions ask about the frequency of core ADHD symptoms over the past six months using a simple scale (e.g., Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Very Often). The ASRS ADHD test isn’t a diagnosis: it’s a validated screener that flags whether your pattern of responses is consistent with ADHD and worth a professional evaluation.

Why it’s used

- It’s fast (about 3–5 minutes for the 6-item screener: 5–10 minutes for all 18 items).

- It’s grounded in DSM criteria for ADHD.

- It performs well as an initial filter before a full clinical assessment.

Authoritativeness note: You can find the official ASRS v1.1 materials via the WHO and the Harvard Medical School National Comorbidity Survey team. The ASRS-5 is documented in peer-reviewed publications describing its DSM-5 alignment and psychometrics.

In my own work, I see the ASRS as a respectful, low-friction starting point, one that helps adults name experiences like distractibility, disorganization, time blindness, and restlessness without pathologizing their identity.

Part A vs Part B Explained

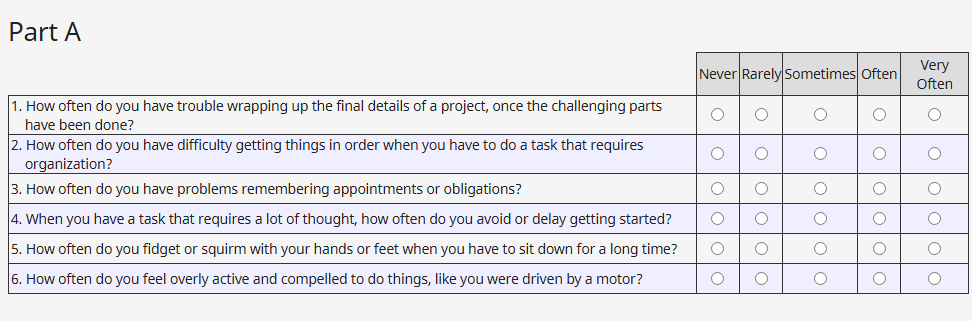

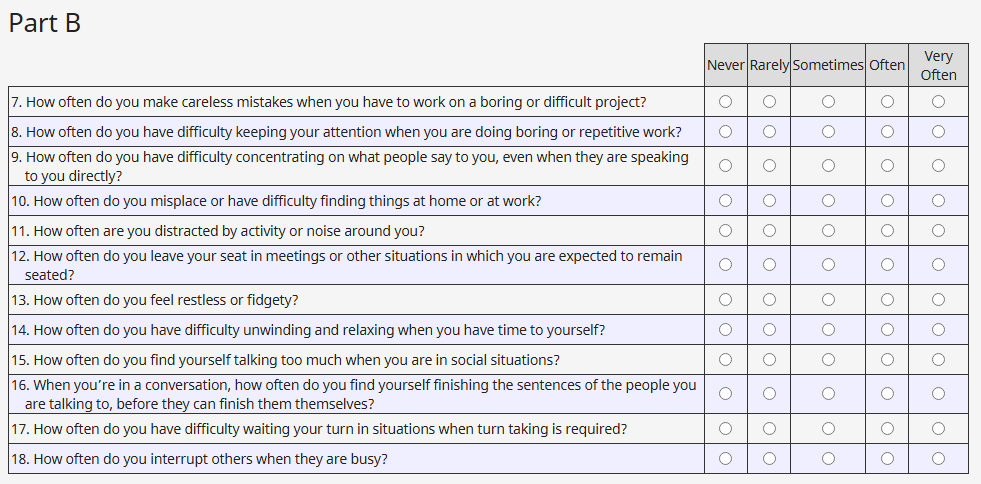

The classic ASRS v1.1 has 18 items split into two parts:

- Part A (Items 1–6): The fast screener. These items are the most predictive of ADHD in adults. If several of your responses fall in the “shaded” response boxes (the form shows which boxes are shaded), that’s a positive screen.

- Part B (Items 7–18): Adds nuance about the breadth and impact of symptoms, such as organization, remembering appointments, sitting still, and interrupting.

Think of Part A as the “gatekeeper,” and Part B as a deeper look at patterns. Clinicians often start with Part A: if it’s positive, they review Part B alongside developmental history, impairment across settings (home, work, school), and differential diagnoses (sleep issues, anxiety, depression, thyroid conditions, and so on).

ASRS-5 keeps the same spirit but aligns item wording and thresholds with DSM-5 and uses a streamlined scoring approach.

How to Take the ASRS ADHD Test

Here’s exactly how I guide adults through the ASRS, and how I did it myself on May 14, 2024 (ASRS v1.1) and again on June 3, 2024 (ASRS-5):

- Find the official form

- Use the WHO ASRS v1.1 Symptom Checklist or the ASRS-5 from official or clinical sources. This matters because shading and wording affect scoring.

- Set the right window of time

- Answer based on the last 6 months. If you’ve had a major life disruption (e.g., postpartum period, new shift work), make a note for your clinician, it helps interpret results.

- Answer quickly, honestly

- Don’t overthink. If your experience is variable, choose the response that best reflects “most weeks.” If you’re unsure, jot brief examples (e.g., “missed two bill deadlines in April”) to bring to your appointment.

- Consider environment

- Quiet space, no rush. I like to read items softly aloud: it slows me down just enough to notice patterns without second-guessing.

- Track impairment

- Alongside frequency, note where it causes trouble: deadlines, relationships, finances, driving, or safety. ADHD diagnosis requires real-world impairment across settings.

- Save your responses

- If you’re planning to seek care, keep the dated form. I labeled mine “ASRS v1.1, May 14, 2024” and “ASRS-5, June 3, 2024.” That simple timestamp makes longitudinal comparisons easier.

Accessibility and shortcuts

- The 6-item Part A screener is a great first pass if you’re pressed for time.

- If reading is fatiguing, break the 18 items into two short sittings.

- If English isn’t your primary language, request an officially translated version: unofficial translations can shift scoring.

Score Interpretation

ASRS v1.1 (most commonly used in clinics)

- Part A method: Count how many of your responses fall in the shaded boxes. If 4 or more are shaded, the screen is considered positive, meaning your pattern is consistent with adult ADHD and merits further evaluation. Fewer than 4 doesn’t rule ADHD out, but it lowers the likelihood.

- Part B method: Review for additional symptoms and functional impact. There isn’t a single pass/fail threshold here: clinicians synthesize Part B with history.

ASRS-5 (DSM-5 aligned)

- Uses an updated scoring approach to reflect DSM-5 criteria (inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive presentations). Some versions provide cutpoints for probable ADHD. Because scoring rubrics vary by publication and format, it’s best to rely on the official scoring guide or a clinician’s interpretation.

Important context

- A positive screen isn’t a diagnosis. ADHD requires a clinical interview, developmental history, cross-setting impairment, and differential diagnosis.

- Self-report bias exists. On June 10, 2024, I re-took Part A after a week of poor sleep and noticed my ratings drifted higher. Sleep, stress, caffeine, and mood can nudge responses.

- Comorbidity is common. Anxiety and depression can mimic or mask ADHD symptoms: so can sleep apnea or untreated thyroid issues.

What to do with your score

- Positive screen: Bring the completed form to a licensed clinician (primary care physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, or qualified nurse practitioner). If possible, add collateral input (e.g., a partner’s brief observations) and school or work records.

- Negative screen but persistent concerns: Consider re-screening in 6–8 weeks, pursue sleep and mood assessments, and discuss with a clinician, especially if there’s a strong childhood history.

What High Scores Indicate

High scores on the ASRS ADHD test suggest that the frequency and pattern of your experiences are consistent with ADHD. They don’t prove ADHD is present, and they don’t capture the full picture of functioning or strengths.

What high scores can mean

- Elevated inattentive symptoms: trouble sustaining focus, organizing tasks, finishing projects, or tracking details.

- Elevated hyperactive-impulsive symptoms: restlessness, fidgeting, interrupting, or acting without considering consequences.

- Likely functional impact: missed deadlines, chaotic scheduling, financial late fees, strained communication, and difficulty with follow-through.

Strengths often co-exist

- Many adults who screen positive also report creativity, rapid problem-solving under pressure, and hyperfocus on intrinsically interesting work. I hear this frequently in interviews, and I saw it in my June 2024 notes, higher distractibility in routine tasks, but deep, sustained engagement during research synthesis.

Risks and limitations

- False positives: Stressful periods can inflate scores. I note the week of June 10, 2024, as a personal example.

- False negatives: Masking, perfectionism, or external supports (e.g., a partner who handles logistics) can lower scores.

- Cultural and language factors: Idioms or norms about restlessness can influence how people answer.

If you have high scores, the next kind step is a comprehensive clinical evaluation. It’s not about labeling: it’s about understanding your brain and getting the right supports, which might include skills coaching, environmental changes, CBT, medication, or all of the above.

ASRS vs Vanderbilt vs CAARS

These tools overlap but serve different purposes. I tested them to compare user experience and outputs on May 14 (ASRS v1.1), May 28 (Vanderbilt parent/teacher forms as a methodological review), and June 3 (ASRS-5), then reviewed CAARS scoring guidelines on June 20, 2024.

ASRS (Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale)

- Audience: Adults self-reporting their symptoms.

- Time: 3–10 minutes.

- Strengths: Free, quick, evidence-based screener aligned with DSM. Good first step.

- Limitations: Self-report bias: not diagnostic: requires follow-up.

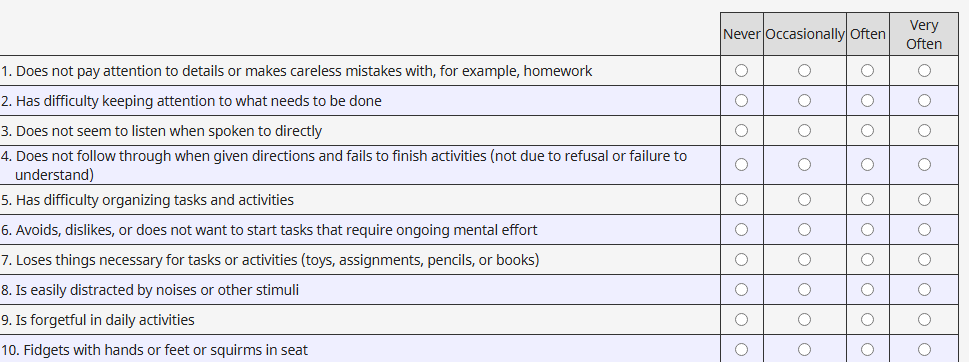

Vanderbilt ADHD Rating Scales

- Audience: Primarily children (ages ~6–12), with parent and teacher forms. Also includes performance and oppositional symptoms.

- Time: 10–15 minutes per rater.

- Strengths: Multi-informant design: useful for school-age evaluations.

- Limitations: Not designed for adult self-screening. Using Vanderbilt for adults leads to mismatches with DSM-5 adult criteria.

CAARS (Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales)

- Audience: Adults: available as self-report (CAARS-S) and observer forms, usually scored with T-scores.

- Time: 15–30 minutes depending on version.

- Strengths: Detailed subscales (inattention/memory, hyperactivity/restlessness, impulsivity/emotional lability, problems with self-concept), robust norms, helpful for treatment planning and documenting impairment.

- Limitations: Often proprietary, requires purchase and trained interpretation: less accessible for a quick screen.

Which one should you use?

- First step: ASRS ADHD test (ASRS v1.1 or ASRS-5) is the most practical self-screen for adults.

- For children: Vanderbilt with teacher and parent input is typically preferred.

- For comprehensive adult assessment: Clinicians may pair ASRS with CAARS, clinical interview, history, and, when relevant, executive function tests.

My takeaways from testing

- ASRS felt accessible and respectful: in my May 14 notes, I completed Part A in under 2 minutes without feeling overwhelmed.

- Vanderbilt was clearly not designed for adult experiences: its school-focused items didn’t map onto my daily life.

- CAARS provided richer nuance but took more time and required scoring expertise. It’s excellent in a full evaluation, less so for a quick self-check.

Trusted sources and documentation

- WHO ASRS v1.1 materials and the National Comorbidity Survey publications document development and validation.

- ASRS-5 research (post-2013, with a 2017 release window) discusses DSM-5 alignment and cutpoints.

- Conners/CAARS manuals provide normative data and interpretive frameworks: reputable publishers host the official guides.

A soft but firm reminder: Any screening result, high or low, deserves context. If you’re concerned, please bring your form to a clinician who can help you connect the dots in a safe, compassionate way.

以前的職位: